Liu Has New Fossil Hamster Species Named in Her Honor

Published May 22, 2018 This content is archived.

story based on news release by ellen goldbaum

A new fossil hamster species unearthed in Tibet has been named after the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences faculty member who discovered it in 2010.

Harsh Conditions Mark Expedition

At the time of the discovery, Juan Liu, PhD, assistant professor of pathology and anatomical sciences, was a doctoral student in paleontology on an expedition in remote Central Asia with several other researchers from Los Angeles and Beijing.

Known as the “roof of the world,” the Tibetan Plateau is an average of 4,950 meters — about 16,000 feet — above the sea.

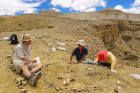

Eager to find new specimens, Liu and her colleagues chose to explore an area called the Zanda Basin, where the combination of high elevation and freezing temperatures create conditions so harsh that expeditions can only take place there during July and August.

“We traveled far away because you have a better chance to discover new things,” Liu says. “The overall elevation in that area is 3,600 meters, so everybody walked slowly, no one was running or jumping because of the extra stress the elevation can put on your body.”

Discovering a Treasure Trove of Fossils

In the early morning of the first working day, Aug. 7, 2010, at Zanda Basin, Liu spotted fragments of bones on a rocky hill.

“I started to call everyone over,” she says. “We all carried walkie talkies so I said, ‘I found something.’ Some were reluctant as they had just jumped out of the vehicle and were eager to prospect fossils. A few others came and we started digging down.”

What they found, she recalls, was a veritable trove of fossils.

“It was filled with bones, teeth, even skulls. It was like a treasure. You would never know it from the surface,” Liu says.

New Genus Name Means ‘High Hamster’

It turned out that among the many findings was a new fossil hamster genus and species. A paper about the new discovery was published earlier this year in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

The genus and species was named Aepyocricetus liuae, with the second word clearly referencing Liu in the etymology of the new species. The paper also describes the etymology of the new genus name; apeys means high in Greek, combined with cricetus, which means living hamster, so the genus name literally means “high hamster.”

Asked how she felt about having a new fossil named for her, Liu says: “I am immensely honored and thrilled. I am a junior faculty member and I am only beginning to make an intellectual contribution to the field. Usually, when a new species is named after someone, it is for a senior colleague in the discipline or a collector with many years of experience. Now I have to live up to the high hamster name.”

Clues to How Mammals Adapted to Climate

According to first author Qiang Li, who praised Liu’s research skills in the field and laboratory, the new fossil was named after her because she discovered the Tibetan locality where these fossil hamster specimens and hundreds of others were collected.

Liu also was a participant at other sites on the harsh Tibetan Plateau, including Qaidam Basin, with an average altitude of as much as 3,000 meters and the Kunlun Pass Basin, with an altitude of approximately 4,600 meters (about 15,000 feet).

She had joined the Tibetan Plateau research group along with Jack Tseng, PhD, assistant professor of pathology and anatomical sciences, and researchers from the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County and the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

The recent publication provides new information about how small mammals adapted to the cold climate and what their migration patterns were on the Tibetan Plateau during the Pliocene Epoch, from about 5.3 million to 2.58 million years ago.